Navigating Uncertainty in GIScience

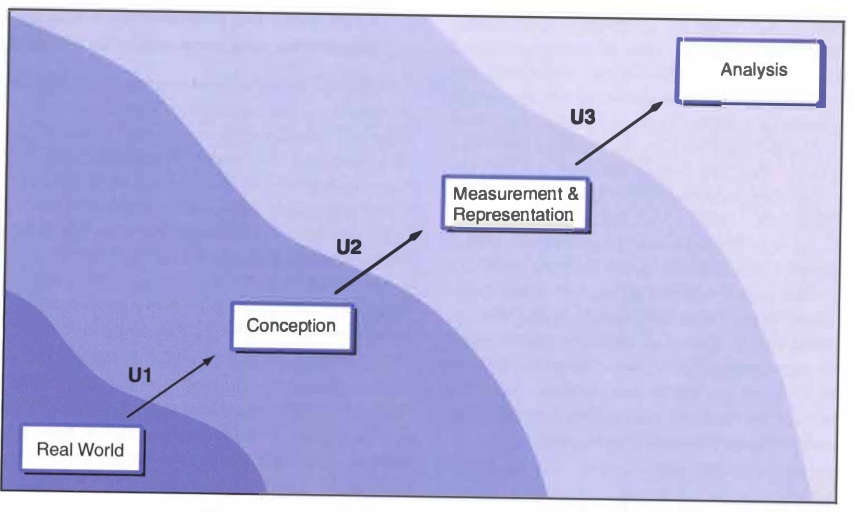

Chapter 6, “Uncertainty,” by Longley et al. (2008) delves into the realm of uncertainty in spatial analysis. This chapter emphasizes the need for a comprehensive understanding of uncertainty to conduct accurate research using spatial analyses. Figure 6.1 in the chapter’s introduction outlines the key steps for spatial analyses and their corresponding filters for error during the research process.

Figure 6.1 “A conceptual view of uncertainty. The three filters, Ul, U2, and U3 can distort the way in which the complexity of the real world is conceived, measured, represented, and analyzed in a cumulative way” (Longely 2008:129).

Figure 6.1 “A conceptual view of uncertainty. The three filters, Ul, U2, and U3 can distort the way in which the complexity of the real world is conceived, measured, represented, and analyzed in a cumulative way” (Longely 2008:129).

Understanding Uncertainty

The first step in dealing with uncertainty pertains to the “conception of geographic phenomena” (Longley 2008:129). In my prior GIS experience in Middlebury GEOG 0261 (Human Geography with GIS), I was less aware of this aspect of uncertainty. Most of our work in that course involved pre-conceived and organized geographic data for practicing various spatial analyses.

Now, with the ability to recognize and articulate errors related to ambiguity, vagueness, fuzziness, and the scale of geographic features, I acknowledge the potential for uncertainty in the conception of some of the data we worked with. This includes rasters of green spaces, flooding data, the conception of racial majority group zones, and indirect indicators like households with cars. My previous focus on spatial data representation also made me aware of aspects of the second step of uncertainty, which involves the “measurement and representation of geographic phenomena”(Longley 2008:136). This encompasses understanding the capabilities and limitations of vector and raster data structures, as well as issues related to classifying data into nominal and ordinal categories .

Structures such as the confusion matrix and statistics like root mean squared error (RMSE) for interval/ratio data further deepened my understanding of how to interpret and identify uncertainties in the representation and conception of spatial data. The third step, “uncertainty in the analysis of geographic phenomena,” partly resonated with the work we did to validate our analyses(Longley 2008:144). This included addressing challenges like the Modifiable Area Unit Problem and the concatenation of datasets. I eagerly anticipate developing a deeper understanding of ways to internally and externally validate spatial analyses through the reproduction studies we are conducting in my current class on open-source GIScience.

The Responsibility of GIS Scientists

It is crucial for GIS scientists to grasp the breadth and depth of uncertainty inherent in spatial analyses. These steps, each representing varying degrees of uncertainty in spatial analysis, must be overcome to advance scientific knowledge. While GIS has historically been used to manipulate data and support specific agendas by overlooking uncertainties, it also possesses powerful capabilities for contributing significant knowledge to the scientific community.

To prevent GIS from regressing to its past uses and ensure its responsible application, each GIS scientist bears the responsibility of identifying and effectively navigating through these spaces of uncertainty. However, this responsibility extends beyond the individual level. Tackling uncertainty requires the collective effort of the GIS community, involving processes like peer review and rigorous validation of new discoveries.

The Role of Open Source and Transparency

This responsibility cannot be seen on purely an individual level. To truly tackle uncertainty, the effort of a broader GIS community is required to follow the process of peer review and interrogate new discoveries to truly test their validity. The world of open source presents the best potential for this community. Processes of internal and external validation must be executable by anyone, in order to collectively conquer uncertainty. This will remain extremely difficult if there is no expectation that all research must be published under the circumstances that it is easily reproducible and replicable.

In conclusion, the all too common uncertainty in GIS work poses the greatest threat to the absolute truth of GIS research and the reputation of GIScience as a discipline; therefore, it should be in the greatest interest of all GIS scientists to identify, tackle, and share all aspects of uncertainty that arise in all forms of spatial analyses.

References Longley, P. A., M. F. Goodchild, D. J. Maguire, and D. W. Rhind. 2008. Geographical information systems and science 2nd ed. Chichester: Wiley. Tullis, J. A., and B. Kar. 2021. Where Is the Provenance? Ethical Replicability and Reproducibility in GIScience and Its Critical Applications. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 111 (5):1318–1328. DOI:10.1080/24694452.2020.1806029